|

The

Batonka Tribe of Zimbabwe

(A National Geographic moment relived)

In 1977, as a young 17 year old

high school graduate from South Africa, and a recently expelled

illegal alien of South Africa returned to Rhodesia, where I was

born, I immediately joined the Armed Forces as a cadet in the

Ministry of Internal Affairs, and was stationed at Binga, on

the edge of Lake Kariba, in Matabeleland Province, where the

original insurgency against the white colonial government of

Ian Smith’s Rhodesia was started back in 1965. It was a

backwater in the terrorist war now, but still lots of action

for a hot blooded young man who knows he is bullet proof and

will live forever. In 1977, as a young 17 year old

high school graduate from South Africa, and a recently expelled

illegal alien of South Africa returned to Rhodesia, where I was

born, I immediately joined the Armed Forces as a cadet in the

Ministry of Internal Affairs, and was stationed at Binga, on

the edge of Lake Kariba, in Matabeleland Province, where the

original insurgency against the white colonial government of

Ian Smith’s Rhodesia was started back in 1965. It was a

backwater in the terrorist war now, but still lots of action

for a hot blooded young man who knows he is bullet proof and

will live forever.

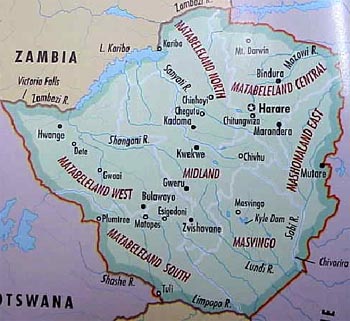

Map of Map of

Zimbabwe

Close up map of Binga, Victoria Falls, Lake Kariba.

Binga was the administrative capital of the tribal trust lands

for the Batonka people… a very small and primitive tribe

of blacks not associated with the two main tribes of Rhodesia,

the Shona and the Matabele. The Batonka tribe, also known as

the Batonga, were very isolated from civilization, in 1977. The

women I saw, when I first arrived in town, were topless, and

the older ones were all smoking large water pipes made from bulbs.

They were smoking dagga, native grown marijuana, and were the

only tribe in Rhodesia who were legally allowed to do so. The

men were wearing loin cloths, and discarded European clothing,

and all had scars on their cheeks, three vertical scars running

down both sides of their faces, huge holes stretched in their

earlobes which were then hung over their ears, and most had pierced

noses with sticks or bones inserted in them. One man I noticed

immediately upon arrival had a toothbrush through his nose. Both

the men and the women had their front teeth removed, both the

upper and the lower set.

Needless to say, having never been around this tribe before,

(or any tribe like this) I was amazed by everything I saw. When

I questioned my colleques about them, I was informed that it

was a cultural condition brought about by centuries of slavery

by the Arab slavers who used to come up the Zambezi river and

steal all the able-bodied men and women to sell on the action

block. The disfigurement was meant to dissuade the Arab slave

traders from taking them. Even though the slave trade had been

stopped by the British since colonial occupation, the practice

was continued to the present day.

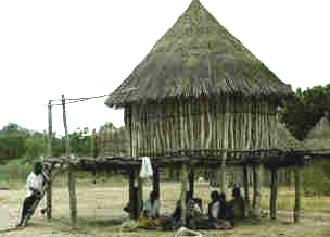

The Batonka were fishermen, and

traditionally lived on the banks of the Zambezi river in stilted

mud huts, (so the crocodiles wouldn’t get them), catching

their fish with long spears made of wood and barbed points made

from metal. The Batonka were fishermen, and

traditionally lived on the banks of the Zambezi river in stilted

mud huts, (so the crocodiles wouldn’t get them), catching

their fish with long spears made of wood and barbed points made

from metal.

Traditional stilt hut.

When the Rhodesian Government dammed the Zambezi river at

Kariba, creating the largest man made lake in Africa at the time,

Lake Kariba, the Batonka had to be relocated away from the flooding

valleys where they had lived and fished for centuries. At first

they were concerned that they would not be able to continue their

traditional lifestyles, but although some things did change,

they were still able to fish, and subsistence farm as they always

had. Life went on as before. The Batonka were separated by the

damming of the Zambezi river, and entire families were separated.

Some now live in Zimbabwe, and some live in Zambia. The war that

followed U.D.I. kept the families from ever re-uniting.

The women would walk sometimes 20 miles to get water, and

I would see them walking along the road balancing the buckets

of water on their heads, in single file, graceful as models,

and timeless as only Africa can be.

There were many occasions when on patrol when I would be totally

surrounded by local tribes people, who were astonished by the

color of my skin, never having seen a white man before, and they

would come up and touch me, and ask questions of my soldiers

who were with me, about me, why I was white, etc… as they

had never seen a white man before. My men always laughed about

it, saying the natives were uncivilized, and ignorant, unlike

them, who were educated, sophisticated and very worldly. And

these same men, who were 20 to 35 years old, would sit around

the campfires at night wide eyed with astonishment when I told

them about such things as skyscrapers, and cities as big as New

York, and Paris. None of them had been 20 miles outside of Binga.

I only wish I had the forethought to take pictures of all

I saw as I rode and walked around my district during the three

and a half years I was stationed there, but I did not. By 1980,

the war was over, and Zimbabwe became an independent country,

free of its colonial shackles.

I immigrated to California, met and married Jamie, my wife

of now 25 years, became an American citizen, and forgot about

Binga, and the Batonka people I had lived with for such a short

time.

Until 1993, when I took Jamie back to Zimbabwe with me for

a first visit ,after being gone 13 years. How time had flown

by in a flash. I knew nothing would be the same, that my home

town, Bulawayo, which was such a beautiful city when I had lived

there back in 1980, would be different; third world, shabby,

run down, black.

Oh, how wrong I was! I could have gone away for a long weekend,

and come back to a few minor changes, such as street name changes,

street vendors selling vegetables on corners that would never

have been allowed in colonial days, more blacks in town and less

whites. But we never felt threatened, overwhelmed, scared to

be out on the streets, anything. It was wonderful. I loved coming

home. I loved showing Jamie my country, which she had only heard

me talking about. We went all over, to the Great Zimbabwe ruins,

to Victoria Falls, where I spent some of my time during the war.

We sailed on the booze cruise on the Zambezi river, watching

the sun go down and listening to the haunting cry of the fish

eagle. We sat for hours and watched the parade of wildlife at

a waterhole in the incredibly beautiful Hwange National Park.

And at night we lay in bed in our tents while lion walked past

our tents searching for scraps, roaring for hours when they had

a kill about one mile away. (Whew, it wasn’t one of us!).

A year before it was a camper they pulled out of a tent and killed

before being chased off by the game rangers.

On our next to last day in Bulawayo, we were at the market

in downtown, in the grounds of the city hall, next to the bustling

bus depot, negotiating wood carvings, and stone beads, and straw

baskets to bring home to the States to sell in our bead store,

when we met these three incredibly handsome young men. They were

about 20 years old, very friendly, well educated, trying to sell

us these beautifully painted masks.

They were constructed with raw sticks cut from trees, tied

together, covered with sacking from maize sacks, and painted

in reds, blacks and whites. They frightened Jamie. The young

men told us they were Batonka ceremonial dancing masks, recreated

for sale to the tourists, hand made by them in the area of Zimbabwe

where they live, a small town on the edge of Lake Kariba, called

Binga. Immediately my warning bells went off….these young

men are trying to pull a fast one over us gullible tourists.

They couldn’t possibly know I was an ex Rhodesian, as my

accent had faded, and my accent now was American, (according

to my Mom, who still lives there, I’m a Yank now), so they

wouldn’t know that I would know they should have scars on

their faces, large holes in their ears, and pierced noses, and

missing front teeth. How dare they cheat us like this! So I immediately

confronted them with my knowledge of the Batonka culture, and

how I came by this knowledge. I’ll show them, the rascals.

Now remember, I already explained how nothing much had changed

in 13 years since I had been gone, and when I stepped off the

plane it could have been just a long weekend, it was that surreal.

So when they had stopped laughing enough to explain to me that

that was their parent’s generation, those 13 years came

roaring back really quickly. Of course! Things had starting changing

back in 1980 when I left Binga at the end of the war. The women

were no longer walking around topless. No-one smoked the water

pipes anymore, I remember now that I had stopped seeing sticks

and bones in the noses of the men almost immediately after I

arrived in Binga, and because most of my contact was with older

men and women, not the children, I always saw the scars and ear

stretchings and missing teeth, but in hind sight now, I realized

that the young children never had their teeth missing. I was

seeing those children all grown up now, and it flashed through

me that I had lived through an incredible moment in time, absolutely

a genuine National Geographic moment. Something that most people

would never have the privilege of seeing, and I know I was truly

blessed to have been able to live it for those incredibly short

three and a half years. Because they have gone, and the culture

of that time has gone, and soon, the memory of that time will

be forgotten.

Africa is an incredible continent – visit it, embrace

it, love it. Never forget it.

|